Peter

Menkhorst was one of the original members of the Orange-bellied Parrot Recovery

Team. An ecologist with Victoria’s

Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE), Menkhorst has a special

interest in little-known and threatened species. Among numerous projects, he is

working on a new field guide to Australian birds, due out in 2014. He continues

to be the Victorian Government representative on the Team.

Menkhorst

is married to Barbara Gleeson; they have two adult children.

What are your first

memories of birding?

I

grew up in the Wimmera, on the edge of the Little Desert. My father was

interested in wildlife and one of his hobbies was photography. By the time I

was seven, I was getting up before dawn and sitting in a hide beside a Malleefowl

mound [breeding chamber of the shy, southern Australian bird], learning to be totally

still and silent.

When he was 12,

Menkhorst’s family moved to bayside Melbourne,

where the first bird he identified was a New Holland Honeyeater. His father gave him a

copy of What

Bird is That? [Australia’s

first birding field guide], which he

studied closely. ‘I knew all those

Neville Cayley plates off by heart!’ he

jokes. After an ‘undistinguished university career’, Menkhorst graduated with a

degree in zoology.

Could you tell me about

your work?

My

first job was in the mammal department at the Museum of Victoria.

It was fantastic. I used the museum collection data – 40,000 mammal specimens –

to try to understand the distribution of mammals across the state.

In

1976, I got a job at the Arthur Rylah Institute [the research arm of the DSE]

doing fauna surveys. For about 15 years, I did fieldwork, trapping and

spotlighting for mammals, capturing reptiles and amphibians and atlassing birds.

Ten of us went out for two weeks at a time. Some years, we did 10 surveys.

At

that time, we didn’t have any idea of the distribution of Victoria’s native fauna, so it seemed

obvious to collate the survey data into the Atlas

of Victorian Wildlife. Victoria was the

first state in Australia

to have an atlas of wildlife and it’s still going.

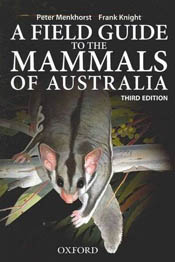

In 1995, partly

based on his mammal surveys, Menkhorst became the principal author and editor

of Mammals

of Victoria, a guide still widely cited as a reference. Another

best-seller followed in 2003 – A Field Guide to the Mammals of Australia, illustrated by Frank Knight and now in its

third edition.

How did you get

involved with the Orange-bellied Parrot?

Until the late 1970s, it had always been a mystery bird. No

one knew anything about it. We knew they turned up around the shores of Port Phillip in winter, and

people saw flocks – sometimes up to 50 – in a few spots. There were old records

of breeding in Tasmania

but no one knew where.

My

first sighting was at the sewage farm (Werribee) in the late 1970s. There were

about a dozen.

World

Wildlife Fund provided money for the Tasmanian Parks & Wildlife Service to

investigate, and that stimulated a whole lot of work, including the formation

of the Recovery Team.

We

were asked if anyone wanted to go to a meeting about this [bird]. No one else

put their hand up so I said, I’ll go! That was in 1983, with people from Tassie, Victoria and South Australia.

Joe

Forshaw, a Commonwealth bureaucrat and parrot expert, chaired the meeting. He

said, ‘Right. We need to form a recovery team like the Americans do. Who wants

to be on it?’ It was the first recovery team in Australia.

From

my wildlife survey work, I’d identified a number of mammals and birds that were

very poorly known. I wanted to help initiate work on them – species such as the

OBP.

Could you

comment on the recovery effort so far and what you would like to see in the

future?

It

hasn’t gone the way we would’ve hoped but we’re still battling on.

In

five years, we want a captive population of 400, spread over at least half a

dozen facilities. We want a wild population persisting. And we’ll hopefully

have started releasing captive-bred birds at Melaleuca again, while there’s

still a wild population there.

If

we have 100

captive pairs (breeding), we’ll be doing well. If we have 400 birds and perhaps

150 pairs breeding, we can produce 300 to 400 birds for release, which is

massively more than we’ve ever had.

Half

of them disappear within a year. Once you get them through that first year,

survival is a lot better.

Some people wonder whether double-clutching might work with OBPs [technique where one clutch of eggs is removed to try to produce a second clutch]. Has it been tried?

We’ve

tried but haven’t had much success. Partly that’s because they’ve evolved to

breed on a fairly high latitude, where the summer is short. They’re not used to

laying two clutches.

There

isn’t time. Being a migratory species, they’ve a fairly short window in

southern Tasmania

to breed. So they’re not really wired to churn out lots of clutches like some other

species, like the Helmeted Honeyeater. We’ve put [OBP] eggs under Blue-wing Parrots. But

the female OBP doesn’t necessarily lay again. They just don’t seem to be geared for

it.

What’s the most

important thing the public can do to help?

Provide

political support. And they can volunteer to search for birds. And we desperately need money.

Finally, why the need

for a new field guide to Australian birds?

There

are four pretty good guides but they were all written in the 1980s and look a

bit dated. We plan several products [such as an app] but initially it’ll be a

book, with fabulous illustrations by three of Australia’s best bird artists, and

scientifically accurate and up-to-date text. I am a co-author with Danny Rogers

and Rohan Clarke.

.JPG)

.jpg)

+(2).jpg)